Avian flu detection in commercial poultry is down, a welcome relief as farms across the country recover from huge losses.

"We lost about 10-and-a-half percent of all the egg-laying population reserves in the United States. So we're getting hit pretty hard," said Yuko Sato, a poultry veterinarian and diagnostic pathologist at Iowa State University.

Detection peaked in January and is now trending downward, following a curve that mirrors bird migration patterns. As warmer weather sweeps across parts of the U.S., the virus’s spread is slowing, and migratory birds are beginning their annual journey to northern breeding grounds.

The highly pathogenic avian influenza has surprised researchers with its resilience and mutations that have jumped to mammals and humans.

"We're seeing this unprecedented thing where when the birds leave, the virus stays," said Matt Hardy, a waterfowl biologist and data scientist with AgriNerds.

AgriNerds is a startup comprised of researchers, veterinarians and data scientists that developed the Waterfowl Alert Network. It's a subscription service for farmers to track concentrations of waterfowl in real-time. The daily predictions and forecasts allow poultry farmers to take preventive measures.

RELATED STORY | This state is offering people $25 to get screened for bird flu

While bird tracking applications exist, the Waterfowl Alert Network focuses on waterfowl, which are reservoir species for the virus.

Hardy said having waterfowl in close proximity to a farm has shown a 3 to 5 times higher likelihood that a farm will experience an outbreak.

Ducks, geese and swans — local waterfowl are retaining the virus in some populations and migratory populations are carrying it with them as they make their annual moves north to south, and back north again.

"If you're a producer in Minnesota, for example, or in North Dakota, knowing when the birds are aggregating in Canada is going to be very important," said Hardy.

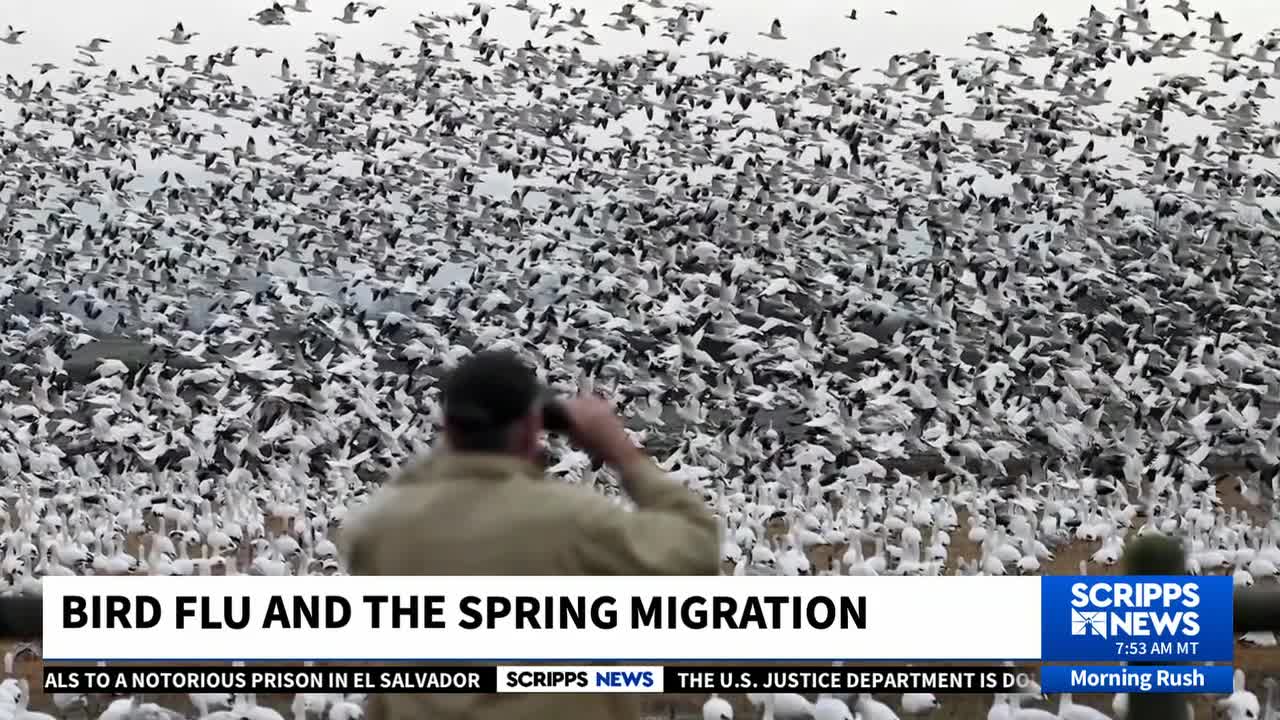

Migratory birds aggregate before migrating, feeding and resting in large groups before beginning their long journeys. The close quarters make great conditions for a highly contagious virus to spread.

The user interface of the Waterfowl Alert Network looks like weather radar — partly because it is. The system relies on publicly available data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The technology was developed in 2022, a branch of a bird tracking system developed at the University of Delaware that can identify biological elements in weather radar.

"So being able to differentiate between a duck or a goose and a raindrop," said Hardy.

It's run by a team of researchers from the East Coast to the West, at the University of Delaware and the University of California. Researchers have mapped the majority of the country and the subscription service has about 1,500 clients in 25 states.

Hardy said innovations like the Waterfowl Alert Network, like much of the bird flu response and research, rely heavily on federal dollars. He's concerned about the government cutbacks that have resulted in a reduced federal workforce and public data that could disappear.

Hardy and his team are working on solutions for the data if it's no longer available, considering archiving it themselves and reaching out to other possible sources. Hardy said it's not about politics, it's about the public having access to data they have a right to.

RELATED STORY | Study finds cheese made with raw milk may contain active bird flu virus

"We're seeing this mixed response to avian influenza virus. We're seeing a lot of money sort of being put into research but then also a lot layoffs at the same time," he said.

It's the same issues Sato is facing in Iowa.

"I've probably lost about four or five collaborators because they're no longer working for these agencies anymore. Those are resources that, unfortunately, I have lost," said Sato.

The USDA announced in early April a "Poultry Innovation Grand Challenge," promising to invest $100 million to winning proposals. It prioritizes three main topics: better understanding the virus to improve responses, treatments for sick poultry and developing vaccines.

It's a grant Sato hopes to get.

"We're at wits' end, the industry is tired of dealing with this outbreak for a very long time. Can we find something that we haven't tried before?"